Back In Time Editing’s newsletter for this month introduces you to the Canada’s role in Confederate espionage activities during the American Civil War. Plus, learn what kind of items were found in a trousseau. Get a peek at the Cable Car Museum in beautiful San Francisco.

Photo courtesy of Openverse.

Vintage Word of the Month: Trousseau

The creation of a trousseau marked a woman’s transition into married life. The word means “bundle,” and in practice, often involved the payment of a dowry. Another form of a trousseau came in a trunk packed with the clothing a bride would bring into her new home. The clothing was often practical, but some of the fashion was for fancy events. As an example, Georgina McDougall, who married Norman Luxton of Banff in 1904, had the following items in her trousseau:

- Grey chiffon evening stole

- Blue silk evening stole

- Beaver coat with matching mitts

- Leather purse

- Silk brocade cape with ostrich plume trim

Source: Inventory of Luxton Residence contents, 1970s. Luxton Historic Home Museum, Banff, Alberta, Canada.

All in all, these trousseaus, or hope chests, reflected a woman’s social status and were used as tools to prepare for marriage. If we were to have a modern equivalent, which essential items do you think should be included in a trousseau?

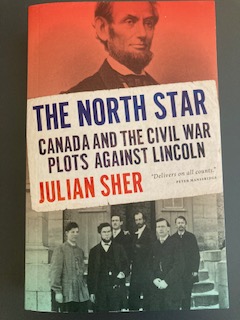

Your Next Great History Read

The North Star: Canada and the Civil War Plots Against Lincoln, by Julian Sher. Alfred A. Knopf Canada, 2023. 465 pp.

British North America’s role in the Underground Railroad before and during the American Civil War helped thousands of people escape from slavery. As a result, BNA, which would become Canada in 1867, is often seen as being on the right side of history during the Civil War. Julian Sher challenges this perception in his latest book, The North Star, by explaining the machinations of Confederate sympathizers operating in Toronto, Montreal, and Halifax.

In Canada, the dominant sentiment was anti-slavery, but this was not so among elites. The following efforts made by aristocrats and other Confederate sympathizers are just a sampling of the overall subterfuge:

- George Taylor Denison III, a Toronto aristocrat who even lived in a plantation-style mansion, welcomed the head of Confederate Secret Service Operations in Canada, Jacob Thompson, into his home, among other high-ranking Confederates.

- Montreal banker Henry Starnes opened and maintained an account which funded Confederate conspiracies. The account held the modern equivalent of tens of millions of dollars. When John Wilkes Booth was killed at the Garrett farm, he was carrying a bank note signed by Starnes.

- After the St. Albans raid, in which twenty-one Confederates robbed three banks in that Vermont town in retaliation for Union activities, the perpetrators fled to Canada. Fourteen were caught, but at the Montreal trial, the Confederate-friendly judge set them free.

Sher bounces back and forth between the villains and heroes of the war. The book is balanced, for instance, by the story of Emma Edmonds, a Canadian-born woman who disguised herself as male to serve a spy in the Union Army. Other powerful accounts include the experiences of doctors Anderson Abbott and Alexander Augusta, who were Canadian and Canadian-trained, respectively. Both men overcame violence and racism during their efforts to serve in the Union Army.

The author’s ability to break a complex web of intrigue into readable sections is impressive, and despite its length, The North Star is a smooth and digestible read. Sher spends little time on analyzing the motives of the Confederates and their sympathizers, but arguably, doing so is unnecessary. Elites in Canada had an affinity for their social counterparts in the U.S. South, and they had the means and will necessary to inflict harm on behalf of the Confederacy. The North Star raises awareness of Canada’s complicity and active role in a horrific chapter of American history, and the book is relevant to our divisive times.

San Francisco Cable Car Museum

1201 Mason Street, San Francisco https://www.cablecarmuseum.org/

San Francisco’s cable car system is a U.S. National Historic Landmark, and millions of people ride the cars every day. The cars look like they’re floating on the road, because their mechanism is hidden under the ground; the only clues to their workings are the steel tracks imbedded into the pavement. The cables along which the cars travel run below the street along these tracks, and the car operator uses a grip system to control the speed of the car, and to brake.

The San Francisco Cable Car Museum is housed inside the powerhouse for the entire cable car network. In addition to the opportunity to enjoy exhibits which explain the history of the system, visitors get to see the huge winding machines which propel the cables along each line. This museum is a full sensory experience. The powerhouse is loud, and the space has an industrial (although not unpleasant!) odour.

It’s worth enduring these minor discomforts, however, since the museum is full of fascinating displays. Your journey on a cable car will be enhanced by this intimate and unique museum, so bring along some earplugs and step into the hub of the operations of this iconic San Francisco historical resource. Pro tip: Hang on tight if you choose to ride on the open sides!

Remember to subscribe to Back In Time Editing Services for more journeys to the past in It’s About Time!

Do you or anyone you know need an editor? Please contact me or share my name. Visit backintimeediting.com to schedule a free introductory session and to learn more about the benefits of hiring an editor for your non-fiction project.

Leave a comment